How are Polpred Models Validated?

Model Validation

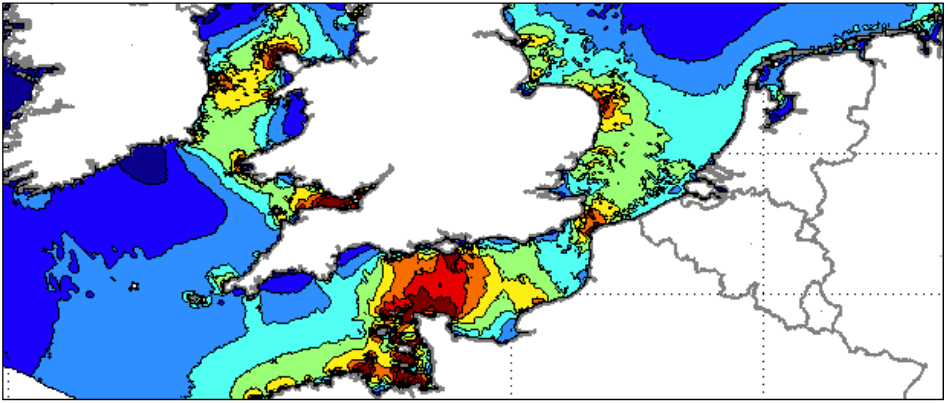

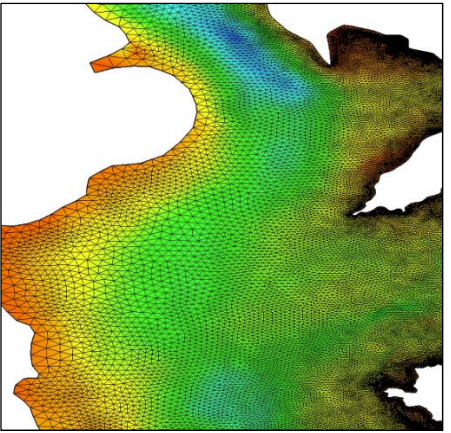

There are a number of standard practices that can be employed to improve model fit to data (model validation). These have arisen largely due to the use of larger area models to provide open boundary forcing for smaller regional models. Whilst the large area model may predict tidal elevations and currents in good agreement with those observed at coastal tide gauges, as the smaller regional models tend to have higher resolution (and hence better representation of the

bathymetry and coastline) they are likely to contain a different volume than the same region in the large area model, and they will therefore respond differently to the same tidal forcing. It is therefore considered reasonable to adjust the tidal forcing extracted from the large model at the open boundaries of the regional model so the predictions of the latter more accurately represent the observations. The open boundary tidal forcing may therefore be adjusted by either increasing or decreasing the imposed tidal constituent amplitude, or by delaying or advancing the imposed phase (e.g. see Young et al., 2000). It is important to note that if a large number of tidal constituents are used to force the model to be validated, the model should be run for a sufficiently long period to separate all the tidal constituents using standard harmonic analysis techniques.

For example, to separate ![]() and

and ![]() the model should be run for at least 29 days. In addition to

the model should be run for at least 29 days. In addition to

adjustments of the boundary forcing, it is common practice to adjust the value of the bottom

friction parameter (within bounds determined by observations). For example, in a three dimensional model with the standard quadratic bottom friction formulation, a bottom friction coefficient of 0.006 for rough sediments such as coarse sand would be appropriate (e.g. Young et al, 2000), whilst for fine muds a lower value of 0.00375 would be considered reasonable (e.g. Aldridge & Davies, 1993).

Some models use a variable bottom friction coefficient to more fully represent the variety of bed

forms and composition within the model domain. A fuller discussion of the dependence of bottom friction on bed form and composition may be found in Soulsby (1983).

References

Aldridge, J.N., Davies, A.M. (1993). ‘A High-Resolution Three-Dimensional Hydrodynamic Tidal

model of the Eastern Irish Sea.’, Journal of Physical Oceanography, 23 (2), 207-224.

Soulsby, R. (1983). ‘The bottom boundary layer in shelf sea.’, In Physical Oceanography of Coastal and Shelf Seas, B. Johns, Ed., Elsevier Oceanography Series 16 35, Elsevier, 189-266.

Young, E.F., Aldridge, J.N. and Brown, J. (2000). ‘Development and validation of a three dimensional curvilinear model for the study of fluxes through the North Channel of the Irish Sea.’ Continental Shelf Research, 20, 997-1035.

![NOCI logo.png]](https://knowledge-software.noc-innovations.com/hs-fs/hubfs/NOCI%20logo.png?height=50&name=NOCI%20logo.png)